Journaling is not just a little thing you do to pass the time, to write down your memories—though it can be—it’s a strategy that has helped brilliant, powerful and wise people become better at what they do.

Oscar Wilde, Susan Sontag, W.H. Auden, Queen Victoria, John Quincy Adams, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Joan Didion, John Steinbeck, Sylvia Plath, Shawn Green, Mary Chestnut, Brian Koppelman, Anaïs Nin, Franz Kafka, Martina Navratilova, and Ben Franklin. All journalers—just to name a few. It was, for them and so many others, as Foucault said, a “weapon for spiritual combat.” A way to practice their principles, be creative and purge the mind of agitation. It was part of who they were. It made them who they were. It can make you better too.

Whether you’re brand new to the concept of journaling or you’ve journaled in the past and fallen out of practice, this ultimate guide to journaling will tell you everything you need to know to help you make journaling one of the best things you do in 2020 and beyond. You’ll learn not only how to journal, but also the about the benefits of journaling, the famous journaling of the past 2,000 years, the best journals to use, and more. Click the links below to navigate to a specific section or scroll and read the entirety of the page:

I. The Benefits Of Journaling

- The Scientific Benefits of Journaling

- Bring Your Problems To A Journal

- Leave Your Destructive Thoughts In A Journal

- Keep A Journal For Your Grandchildren

- Journal For Your Future Self

- Forget All The Rules About Journaling. Do What Works.

II. How To Journal

- Start Small

- Track Something In Your Journal

- Use Your Journal To Prepare In the Morning

- Use Your Journal To Review Your Day In The Evening

- Copy Down Important Quotes In Your Journal

- Brainstorm Ideas In Your Journal

- The Bullet Journal Method

III. Famous Journalers Throughout History

IV. The Best Journals To Use

V. Additional Journaling Resources

If you want to take a deeper dive into Stoicism and learn how to apply the philosophy to your life, check out our most popular course, Stoicism 101: Ancient Philosophy For Your Actual Life. It’s a 14-day course that will equip you with the tools to live as vibrant and expansive a life as the Stoics. Along with 14 daily emails, there will be 3 live video sessions with bestselling author Ryan Holiday, one of the world’s foremost thinkers and writers on ancient philosophy and its place in everyday life. Learn more here and make sure to register before the live cohort begins on March 22nd!

***

Listen to “The Art of Journaling” as read by Ryan Holiday:

I. The Benefits of Journaling

The Science-Backed Benefits of Journaling

The scientific research to support journaling is extensive and compelling:

[*] According to a study conducted by Harvard Business School, participants who journaled at the end of the day had a 25% increase in performance when compared with a control group who did not journal. As the researchers conclude, “Our results reveal reflection to be a powerful mechanism behind learning, confirming the words of American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer John Dewey: ‘We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience.’”

[*] Another Study by Cambridge University found journaling helps improve well-being after traumatic and stressful events. Participants asked to write about such events for 15–20 minutes resulted in improvements in both physical and psychological health.

[*] Improved Communication Skills — A Stanford University study found the critical relationship between writing and speaking. Writing reflects clear thinking, and in turn, clear communication.

[*] A study by The Journal of Social and Personal Relationships found that writing “focused on positive outcomes in negative situations” decreases emotional distress.

[*] Improved Sleep —The Journal of Experimental Psychology found that journaling before bed decreases cognitive stimulus, rumination, and worry, allowing you to fall asleep faster.

[*] Boosted Cognition — Research published to the Journal of Experimental Psychology found that reflective writing reduces intrusive and avoidant thoughts about negative events and improves working memory. These improvements in turn free up our cognitive resources for other mental activities, including our ability to cope more effectively with stress

Bring Your Problems To Your Journal

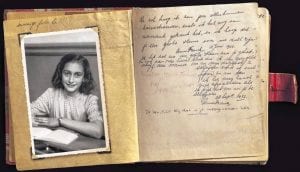

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank made her first entry to her famous, existentially essential diary, “I hope you’ll be a great source of comfort and support.” Twenty-four days after that first entry, Anne and her Jewish family were forced into hiding, in the cramped attic annex over her father’s warehouse in Amsterdam. It’s where they would spend the next two years. According to Anne Frank’s father, Otto, Anne didn’t write in her journal every day. She wrote when she was upset or dealing with a problem. She wrote when she was confused. She wrote in that journal as a form of therapy, so as not to unload her troubled thoughts on the family and compatriots with whom she shared such unenviable conditions. One of her best and most insightful lines must have come on a particularly difficult day. “Paper,” she said, “has more patience than people.”

In the Research section of this piece, we mentioned one study that proved how journaling helps improve well-being after traumatic and stressful events. Similarly, a University of Arizona study showed that people were able to better recover from divorce and move forward if they journaled on the experience. Keeping a journal is a common recommendation from psychologists as well, because it helps patients stop obsessing and allows them to make sense of the many inputs—emotional, external, psychological—that would otherwise overwhelm them. For instance, Shia LaBeouf’s court-mandated journaling on his childhood trauma became the screenplay for the critically acclaimed Honey Boy. “It was part of sussing out my past, flashlight to your soul, trying to get to know myself, like a shedding of skin in a way,” LaBeouf said of how journaling became his therapy. “One of the more effective acts of self-care is also, happily, one of the cheapest,” as Hayley Phelan of the New York Times wrote of starting her journaling practice at a time when “I was in a place where I would have tried anything to feel better.”

Your journaling is not your performing for history. It’s you reflecting. It’s you working through your problems. It’s you figuring things out and clearing your head. Write about the maddingly frustrating people you encountered today. The comment, the tweet, the news headline that made you furious. Write about the wounds you still carry from childhood. The person who didn’t treat you right. The terrible experience. The parent who was just a little too busy or a little too critical or a little too tied up dealing with their own issues to be what we needed. The sources of anxiety or worry, the frustrations that routinely pop up at the worst times, the reasons you have trouble staying in relationships, whatever problem you are dealing with—take them to your journal. You’ll be shocked by how good you feel after.

Leave Your Destructive Thoughts In Your Journal

Eugène Delacroix—who called Stoicism his consoling religion—struggled as we all struggle with occasional, even frequent internal tormenting: “My mind is continually occupied in useless scheming…They burn me up and lay my mind to waste. The enemy is within my gates.” Later he writes, “I am taking up my Journal again after a long break. I think it may be a way of calming this nervous excitement that has been worrying me for so long.” As Tim Ferriss has said of his daily journaling habit, “I don’t journal to ‘be productive.’ I don’t do it to find great ideas, or to put down prose I can later publish. The pages aren’t intended for anyone but me…I’m just caging my monkey mind on paper so I can get on with my fucking day.”

Yes! That is what journaling is about. Instead of carrying that baggage around in our heads or hearts, we put it down on paper. It’s spiritual windshield wipers, as the writer Julia Cameron once put it. I’ve written about how taking something I was angry about to my journal kept me from doing something stupid, something I would have regretted. Lincoln’s called them “hot letters”—whenever he felt a pang of anger towards someone, he would grab a pen and a blank piece of paper and spill his pent-up rage onto the page. Then he’d write, “Never sent. Never signed.”

“Constantly down the list of those who felt intense anger at something: the most famous, the most hated, the most whatever,” Marcus Aurelius wrote. “And ask: Where is all that now? Smoke, dust, legend…or not even legend.” We all carry around destructive thoughts. About the things that went wrong. The people who hurt us. The mistakes we’re embarrassed about. The promises we made and then broke, or that were made to us and then broken by someone else. The love interest who had no interest. The business partner who screwed us over. It all adds up. It builds and builds, burning us up inside. Don’t turn into smoke, dust, or legend, like so many people in history. Burn it out of yourself and onto the pages of journal.

Keep A Journal For Your Grandchildren

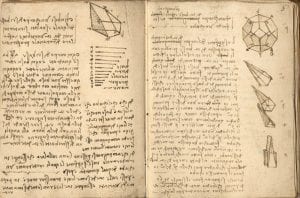

In Walter Isaacson’s wonderful biography of Leonardo Da Vinci, he spends a lot of time dissecting and exploring the ideas in Da Vinci’s notebooks. As Isaacson observed of Da Vinci’s lifelong habit of journaling: “Five hundred years later, Leonardo’s notebooks are around to astonish and inspire us. Fifty years from now, our own notebooks, if we work up the initiative to start them, will be around to astonish and inspire our grandchildren, unlike our tweets and Facebook posts.” Paper, Isaacson has said, is the best technology ever invented. Marcus Aurelius is example of this. The American philosopher Brand Blanshard was as enthralled with Marcus’s writing as Isaacson was with Da Vinci. As he said:

“Few care now about the marches and countermarches of the Roman commanders. What the centuries have clung to is a notebook of thoughts by a man whose real life was largely unknown who put down in the midnight dimness not the events of the day or the plans of the morrow, but something of far more permanent interest, the ideals and aspirations that a rare spirit lived by.”

Stop wasting your time tweeting and chattering and texting and snapchatting. Or at least steal some of that time to start producing your own notebooks. Create something that, if the centuries don’t cling to, at least your family can. Issacson again: “They’ll be around 50 years for…your grandchildren or great-grandchildren. They’ll be around maybe 500 years.”

Journal For Your Future Self

If your grandchildren don’t care, produce something that will give you something to look back on and learn from. The musician, producer, circus performer, entrepreneur, TED speaker, and author, Derek Sivers, wrote an article that began, “You know those people whose lives are transformed by meditation or yoga or something like that? For me, it’s writing in my diary and journals. It’s made all the difference in the world for my learning, reflecting, and peace of mind.” For over 20 years, every night, Sivers takes just a couple minutes to jot down a few sentences to recap his day, how he felt, and thoughts he had. What’s so transformational about that? As Sivers explains:

“We so often make big decisions in life based on predictions of how we think we’ll feel in the future, or what we’ll want. Your past self is your best indicator of how you actually felt in similar situations. So it helps to have an accurate picture of your past. You can’t trust distant memories, but you can trust your daily diary. It’s the best indicator to your future self (and maybe descendants) of what was really going on in your life at this time. If you’re feeling you don’t have the time or it’s not interesting enough, remember: You’re doing this for your future self. Future you will want to look back at this time in your life, and find out what you were actually doing, day-to-day, and how you really felt back then. It will help you make better decisions.”

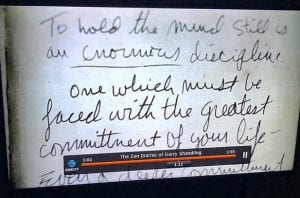

How often do you consult your past self to make decisions? Could you do so even if you wanted to? Or have most days, most experiences, most feelings, most thoughts vanished from memory? Journaling is a memory bank with unlimited storage. It’s an archive, a reference manual, an unmatched tool for learning from today to inform tomorrow. That’s why journaling is so transformational. “Journaling,” Maria Popova—dedicated diarist with “an irresistible fascination with the diaries of artists, writers, scientists, and other celebrated minds”—has written, “is a practice that teaches us better than any other the elusive art of solitude — how to be present with our own selves, bear witness to our experience, and fully inhabit our inner lives.

Forget All The Rules About Journaling. Do What Works.

What’s the best way to start journaling? Is there an ideal time of day? How long should it take? How many pages?

Forget all that. Who cares? How you journal is much less important than why you are doing it: To get something off your chest. To have quiet time with your thoughts. To clarify those thoughts. To separate the harmful from the insightful. To prepare for the day ahead and review the day that passed. There’s no right way or wrong way. The point is just to do it.

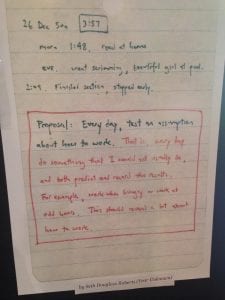

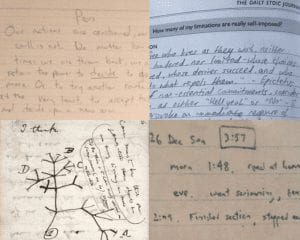

When Charles Darwin began keeping his “little diary” at the age of 29, he filled the pages with everything he could remember from his life, until eventually, he was up to date and shifted his journaling to daily notable events. Thomas Edison made it his objective to record the most mundane events and details of his day. “Went into a drug store and bought some alleged candy, asked the gilded youth with the usual vacuous expression, if he had any nitric peroxide, he gave a wild stare of incomprehensibility,” Edison wrote on July 19, 1885. Mark Twain had a section in his journals for dirty jokes. General George S. Patton had a section for his daily affirmations, like “Do your damdest always,” “Always do more than is required of you,” and “You can be what you will to be.” Thomas Jefferson’s morning journaling routine began taking weather measurements, such as temperature, wind speed, and precipitation. Beethoven liked to sometimes use his journal to write what he wish he would have said in a prior conversation. Hemingway brought his journal everywhere, recording expenses and, more bizarrely, tracking his wife’s menstrual cycles. Ben Franklin used his journal to chart his progress with his personally constructed improvement program of living his thirteen virtues. George Marshall jotted down the names of everyone he met in his journal and made notes of the character traits he observed. Leonardo da Vinci’s habit was to write little fables to himself. Susan Sontag typically journaled lists—movies seen, books read or to read, places to eat and drink, cities she hoped to visit, notable artists, words and phrases she liked. And as Viginia Woolf’s husband observed in the introduction to Woolf’s collected journals, A Writer’s Diary, she used her journal for “practicing or trying out the art of writing.”

There are no rules in journal writing. The pages are for your eyes only. Be your weirdest self. Be your most curious self. Be your most prolific horrible idea-having self. Dump out everything and anything that comes to mind. There’s no one way to journal. There’s no right way to journal. There’s only your way of journaling. Make it weird. Make it fun. Just do it.

And if you’ve started before and stopped, start again. Getting out of the rhythm happens. The key is to carve out the space again, today. The French painter Eugène Delacroix—who called Stoicism his consoling religion—struggled as we struggle:

I am taking up my Journal again after a long break. I think it may be a way of calming this nervous excitement that has been worrying me for so long.

Yes! That is what journaling is about. It’s a few minutes of reflection that both demands and creates stillness. It’s a break from the world. A framework for the day ahead. A coping mechanism for troubles of the hours just past. A revving up of your creative juices, for relaxing and clearing. Once, twice, three times a day. Whatever. Find what works for you. Just know that it may turn out to be the most important thing you do all day.

II. How To Journal

Start Small

The writer James Clear talks a lot about the idea of “atomic habits”—a small act that makes an enormous difference in your life. It started with an idea he learned about habit formation from Leo Babatua. Leo’s advice to people who want to get in the habit of flossing daily? Start by flossing just one tooth a day. Or if you want to start exercising regularly: start with 1-2 minutes a day. Or if want to eat healthy: eat one vegetable a day. Or if you want to read more: read one page a day. “Of course, that seems so ridiculous most people laugh,” Leo says, “But I’m totally serious: if you start out exceedingly small, you won’t say no. You’ll feel crazy if you don’t do it. And so you’ll actually do it!”

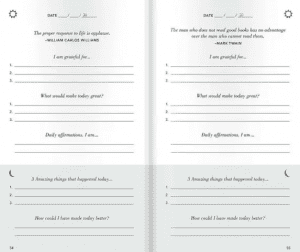

That’s why my journaling routine starts with the One Line a Day Journal. Tim Ferriss similarly starts in the 5-Minute Journal, which “I use for prioritizing and gratitude,” Tim explained. “The 5MJ is simplicity itself and hits a lot of birds with one stone: Five minutes in the morning of answering a few prompts, and then five minutes in the evening doing the same…Think of it as my boot-up sequence for an optimal day. The rest varies wildly, but the first 60 to 90 minutes after waking are what I focus on most.”

Your journaling does not need to produce Nobel Prize-worthy prose. You don’t need to commit to a life practice right now. Start with one line—about how you are feeling, something you did yesterday, something you are excited about, someone you are thinking about. Start by doing it for one week. Start by writing a few things you are grateful for. Start with a sentence about the mindset you are going to attack the day with, about something interesting you learned in your reading yesterday, about your plans for the day. Whatever it is, start ridiculously small. You’ll know when you’re ready to build on it and write in more depth.

Track Something In Your Journal

Most people drop the journaling habit, or never begin, out of intimidation. The blank page is scary. Where do I even start? I have nothing important to say. Take the pressure off by creating an easy metric to track each day as the first line of your journal entry. After the One Line a Day Journal, in a black moleskine, I journal quickly yesterday’s workout (how far I ran or swam), what work I did, any notable occurrences, and some lines about what I am grateful for, what I want to get better at, and where I am succeeding.

James Clear records his pushups and reading habits. Nobel Prize winner Danny Kahneman suggests keeping track of the decisions you’ve made in your journal. Neuroscientist Dr. Tara Swart lists what she is grateful for and what she accomplished. Bestselling author and avid runner David Epstein tracks workouts and training goals. Tim Ferriss has recorded every workout he’s done since the age of 15. Bestselling author and artist Austin Kleon keeps a logbook — writing down each day a simple list of things that have occured. Who did he meet, what did he do, etc. Why? For the same reason many of us struggle with keeping a journal: “For one thing, I’m lazy. It’s easier to just list the events of the day than to craft them into a prose narrative. Any time I’ve tried to keep a journal, I ran out of steam pretty quick.”

You can track what time you woke up and how many hours of sleep you got. You can log everything you ate that day. You can record the tasks you accomplished at work yesterday. The point is to know exactly where to begin when you open to the blank page each day.

Use Your Journal to Prepare In the Morning

Despite his admitted struggles to get out of his warm, comfortable bed, Marcus Aurelius seems to have done his journaling first thing in the morning. From what we can gather, he would jot down notes about what he was likely to face in the day ahead. He talked about how frustrating people might be and how to forgive them, he talked about the temptations he would experience and how to resist them, he humbled himself by remembering how small we are in the grand scheme of things, and journaled on not letting the immense power he could wield that day corrupt him.

Who knows what kind of emperor, what kind of man, Marcus would have been without that preparation? Instead of letting racing thoughts run unchecked or leaving half-baked assumptions unquestioned, he forced himself to write and examine them. Putting his own thinking down on paper let him see it from a distance. It gave him objectivity that is so often missing when anxiety and fears and frustrations flood our minds. It let him enter his day and the important work calm and centered.

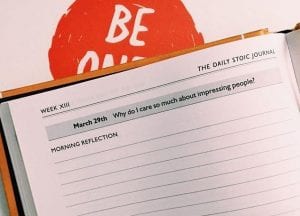

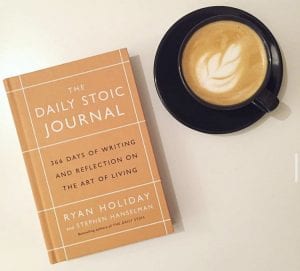

My morning journaling concludes in The Daily Stoic Journal where I prepare for the day ahead by meditating on a short prompt. Marcus said, “When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil.” I think about all the things that I’m going to face in the day and how I want to be ready for them and how I want to respond to them. “A healthy mind should be prepared for anything,” Marcus was reminding himself.

What I am really doing with The Daily Stoic Journal is setting an intention or a goal for the day. Maybe it’s that I don’t want to lose my temper or my patience when I go talk to my neighbor about something that’s been bothering me. Maybe it’s that I want to make more time for stillness than I’ve been able to lately. Maybe it’s that I want to get the draft of an article finalized. It doesn’t need to be some lofty, earth-shattering goal. The point is to give myself something I can review at the end of the day–that I can actually evaluate myself against. More on that next.

Use Your Journal To Review Your Day In The Evening

Unlike Marcus, Seneca seemed to do most of his journaling and reflection in the evening. As he wrote, “When the light has been removed and my wife has fallen silent, aware of this habit that’s now mine, I examine my entire day and go back over what I’ve done and said, hiding nothing from myself, passing nothing by.” He would ask himself whether his actions had been just, what he could have done better, what habits he could curb, how he might improve himself. Winston Churchill was famously afraid of going to bed at the end of the day having not created, written or done anything that moved his life forward “Every night,” he wrote, “I try myself by Court Martial to see if I have done anything effective during the day. I don’t mean just pawing the ground, anyone can go through the motions, but something really effective.” That’s what the path to greatness requires. Self-awareness. Self-reflection.

It’s also what journaling is uniquely suited to help you do.

The founder of Linkedin, Reid Hoffman, jots down in his notebook things that he likes his mind to work on overnight. Similarly, chess prodigy and martial arts phenom Josh Waitzkin, has a similar process: “My journaling system is based around studying complexity. Reducing the complexity down to what is the most important question. Sleeping on it, and then waking up in the morning first thing and pre-input brainstorming on it. So I’m feeding my unconscious material to work on, releasing it completely, and then opening my mind and riffing on it.”

Dutch scientist Marije Elferink-Gemser studied the qualities that helps people get past performance plateaus and found that “Reflection is…a key factor in expert learning and refers to the extent to which individuals are able to appraise what they have learned and to integrate these experiences into future actions, thereby maximizing performance improvements.”

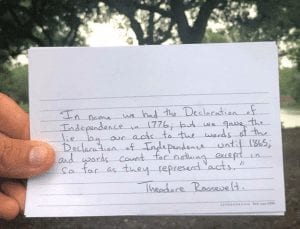

Copy Down Important Quotes In Your Journal

In Meditations, Marcus Aurelius twice quotes from the comedies of Aristophanes, the Athenian comic playwright. Half a dozen times, we see him quote the tragedies and plays of Euripides, as well as the teachings of Epictetus. He quotes the tragedian Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. He quotes philosophers Democritus, Epicurus, and Plato. He quotes the poets Empedocles, Pindar, and Menander. As author Steven Johnson said,

“Scholars, amateur scientists, aspiring men of letters—just about anyone with intellectual ambition…was likely to keep a commonplace book. In its most customary form, “commonplacing,” as it was called, involved transcribing interesting or inspirational passages from one’s reading, assembling a personalized encyclopedia of quotations.”

Petrarch kept one. Montaigne, Thomas Jefferson, Napoleon, Ronald Reagan, Charles Darwin, Mark Twain, Ludwig van Beethoven—they all kept a journal, a depository of quotes and anecdotes. According to his biographer, the author and columnist H.L. Mencken “methodically filled notebooks with incidents, recording straps of dialog and slang,” and favorite bits from newspaper columns he liked. Record what strikes you, quotes that motivate you, stories that inspire you for later use in your life, in your business, in your writing, in your speaking, or whatever it is that you do.

In his book, Old School, Tobias Wolf’s semi-autobiographical character takes the time to type out quotes and passages from great books to feel great writing come through him. I do this almost every weekend in a separate journal I call a “commonplace book” that is a collection of quotes, ideas, stories and facts that I want to keep for later. It’s made me a much better writer and a wiser person. I am not alone. In 2010, when the Reagan Presidential Library was undergoing renovation, a box labeled “RR’s desk” was discovered. Inside the box were the personal belongings Ronald Reagan kept in his office desk, including a number of black boxes containing 4×6 note cards filled with handwritten quotes, thoughts, stories, political aphorisms, and one-liners. They were separated by themes like “On the Nation,” “On Liberty.” “On War,” “On the People,” “The World,” “Humor,” and “On Character”. This was Ronald Reagan’s version of a commonplace book. Robert Greene, detailing his reading and notetaking process, writes: “When I read a book, I am looking for the essential elements in the work that can be used to create the strategies and stories that appear in my books…I then go back and put these important sections on notecards.” Lewis Carroll, Walt Whitman, Thomas Jefferson all kept their own version of a commonplace book.

Brainstorm Ideas In Your Journal

Ludwig van Beethoven was rarely seen without his notebook, not even when out to drinks with friends. One of his biographers, Wilhelm Von Lenz, wrote in 1855, “When Beethoven was enjoying a beer, he might suddenly pull out his notebook and write something in it. ‘Something just occurred to me,’ he would say, sticking it back into his pocket. The ideas that he tossed off separately, with only a few lines and points and without barlines, are hieroglyphics that no one can decipher. Thus in these tiny notebooks he concealed a treasure of ideas.”

Pliny the Younger, a prominent lawyer and prolific writer in ancient Rome, was another to keep a notebook always at hand. In one letter to the eminent senator and historian Cornelius Tacitus, Pliny describes a morning hunting trip. “I was sitting by the hunting nets with writing materials by my side,” he writes, “thinking something out and making notes, so that even if I came home emptyhanded I should at least have my notebooks filled. Don’t look down on mental activity of this kind, for it is remarkable how one’s wits are sharpened by physical exercise; the mere fact of being alone in the depths of the woods in the silence necessary for hunting is a positive stimulus to thought. So next time you hunt yourself, follow my example and take your notebooks along with your lunch-basket and flask; you will find that Minerva walks the hills no less than Diana.”

Thomas Edison kept a notebook titled “Private Idea Book” in which he kept different ideas that popped into his head, possible inventions he’d later work on, such as “artificial silk” or “ink for the blind” or “platinum wire ice cutting machine.”

Entrepreneur and Bestselling author James Altucher carries with him a waiter’s pad and forces himself to come up with at least ten ideas per day. “Most people don’t realize this: The idea muscle is a real muscle,” says Altucher. “And it atrophies super quickly.”

Before Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species became a book that altered our understanding of biology, natural sciences, and several other disciplines of human knowledge, it was just a running list of thoughts, observations, and lessons learned throughout the day that Darwin recorded in his journals. Regardless of whether it was on index cards or in journals or a waiter’s pad—the Twains, the Darwins, the Beethovens of the world weren’t some innate geniuses. They were exercising their idea muscle every day.

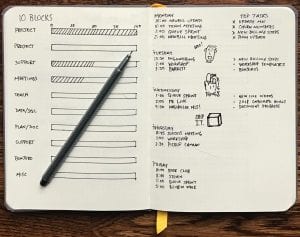

The Bullet Journal Method

Epictetus uses the word ataraxia fourteen times in the Discourses and twice in the Enchiridion. Epictetus said it is the fruit of following philosophy. It means tranquility or freedom from disturbance by external things. It is the state of mind and being that the Stoics aspired to. It is a state free of clutter and chaos. And, it is a state of being that is never not hard to achieve, because each day presents plenty of opportunities to clutter or minds—responsibilities, the dysfunctional job that stresses you out, a contentious relationship, reality not agreeing with your expectations. We’re anxious, then we’re scared, then sad, then angry. Then we spiral. We lose control. Our problems compound. We drift further and further from ataraxia.

If only there were a tool to help us declutter our minds. Well, The Bullet Journal Method has helped thousands and thousands of people do just that. BuJo, as the loyal practitioners call it, has become known as the “KonMari for your racing thoughts.” The method was created by Brooklyn-based digital product designer and art director Ryder Carroll, who, after being diagnosed with ADD, committed years to figuring out a way to organize and sort information conducive to the workings of his scattered mind. As it turned out, the method he created is conducive to the workings of all our scattered minds. Carroll didn’t just create a journaling method. He created a movement. There’s blogs, social media accounts, YouTube channels, a subreddit community—all with massive followings and all dedicated entirely to BuJo.

So what is BuJo? Carroll calls it “a mindfulness practice disguised as a productivity system,” with only one goal: intentional living. “weeding out distractions and focusing your time and energy in pursuit of what’s truly meaningful, in both your work and your personal life. It’s about spending more time with what you care about, by working on fewer things.” “If you seek tranquillity,” Marcus Aurelius journaled, “do less.” And then he followed with some clarification. Not nothing, less. Do only what’s essential. “Which brings a double satisfaction,” he writes “to do less, better.” That’s the point of BuJO: to get a taste of that tranquillity Marcus was talking about and that ataraxia Epictetus was talking about, which is were proponents of it.

All you need to get started is a blank notebook. We do recommend watching the video below if you’re brand new to the BuJo system. But, ultimately, Carroll says, “The only thing that the bullet journal needs to be is effective, and how it can best serve its author is entirely up to them.”

III. Famous Journalers Throughout History

Several of history’s most devout journalers have appeared throughout this piece. The list of people, ancient and modern, who practiced the art of journaling is comically long and fascinatingly diverse. You could fill books and books, but here are our top 5:

Marcus Aurelius

“The recognition that I needed to train and discipline my character. Not to be sidetracked by my interest in rhetoric. Not to write treatises on abstract questions, or deliver moralizing little sermons, or compose imaginary descriptions of The Simple Life or The Man Who Lives Only for Others. To steer clear of oratory, poetry and belles lettres. Not to dress up just to stroll around the house, or things like that. To write straightforward.” — Marcus Aurelius

A little less than two thousand years ago now, in the morning from inside his tent on the front lines of the war in Germania, a man named Marcus Aurelius, the emperor of the Roman Empire, sat down with ink and papyrus and jotted down reminders and aphorisms of Stoic thinking to himself. Where did he learn to do this journaling? Whose model was he following? We don’t know. Perhaps it was Epictetus, a former slave who had become a Stoic philosopher, who had taught that everyday we should keep our philosophical aphorisms and exercises at hand, that we should “write them, read them aloud, talk to yourself and others about them.” Or maybe it was Seneca, another Stoic, who spoke about putting our lives up for review, and journaling about where we can improve.

In any case, this few minutes he spent alone with a journal in the morning were not just relaxing, they helped make him one of the greatest men the world had ever seen. Matthew Arnold, the essayist, remarked in 1863, that in Marcus we find a man who held the highest and most powerful station in the world—and the universal verdict of the people around him was that he proved himself worthy of it. Machiavelli considers the time of rule under Marcus the “golden time” and coined Marcus the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” And the private thoughts of one of the world’s greatest figures—about how to live well, about how to overcome adversity, about how to deal with frustrating people, about how to combat negative thinking, about how to make good on the responsibilities and obligations, about everything related to the human experience—survives to us. Meditations is perhaps the only document of its kind ever produced. And that it survives two thousand years later is a miracle and treasure.

Anne Frank

“For someone like me, it is a very strange habit to write in a diary. Not only that I have never written before, but it strikes me that later neither I, nor anyone else, will care for the outpouring of a thirteen year old schoolgirl.” — Anne Frank

For her thirteenth birthday, a precocious German refugee named Anne Frank was given a small red-and-white “autograph book” by her parents. Although the pages were designed to collect the signatures and memories of friends, she knew from the moment she first saw it in a store window that she would use it as a journal. “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone,” Anne’s first lines in the small book read. Journaling guided Anne Frank through unimaginable adversity. In that journal, we hear of the timeless plight of the refugee, we are reminded of the humanity of every individual (and how societies lose sight of this) and we are inspired — even shamed — to see the cheerful perseverance of a child amidst circumstances far worse than any of us could ever know.

Henry David Thoreau

“Is not the poet bound to write his own biography? Is there any other work for him but a good journal? We do not wish to know how his imaginary hero, but how he, the actual hero, lived from day to day.” — Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau—like his friend, mentor, and fellow journaler, Ralph Waldo Emerson—used the word “poet” more generally than we’ve come to use and think of the word. He believed we are all poets. We are all trying to discover the truth of our experience. We are all pining to articulate what we believe and feel. And there is no better medium to discover ourselves, he believed, than in a journal. Proof of that belief is the 2-million-word journal that he kept starting at the age of 20 in 1837 until six months before he died in 1862.

Mark Twain

“Keeping a journal is the veriest pastime in the world, and the pleasantest…Only those rare natures that are made up of pluck, endurance, devotion to duty for duty’s sake, and invincible determination, may hope to venture upon so tremendous an enterprise as the keeping of a journal.” — Mark Twain

When Mark Twain was 21, a teacher told him, “My boy, you must get a little memorandum-book; and every time I tell you a thing, put it down right away.” This, Twain writes in Life On The Mississippi, was a “revelation to me; for my memory was never loaded with anything but blank cartridges.” He’d go on to fill somewhere around 50 notebooks, filled with witty thoughts and potent observations on the human condition that heavily influenced his writing.

Anaïs Nin

“I believe I could never exhaust the supply of material lying within me. The deeper I plunge, the more I discover. There is no bottom to my heart and no limit to the acrobatic feats of my imagination.” — Anaïs Nin

“People look for retreats for themselves in the country, by the coast, or in the hills,” Marcus Aurelius journaled. “There is nowhere that a person can find a more peaceful and trouble-free retreat than in his own mind…So constantly give yourself this retreat, and renew yourself.” There is perhaps no one in documented history who followed those words more religiously than Anaïs Nin. She was a prolific writer, but her most-cherished artworks are her journals. Nin began her first journal in 1914 at the age of eleven and kept journaling until her death 63 years later in 1977. In the end, she sixteen volumes of Nin’s journals were published.

IV. The Best Journals To Use

The Artist’s Way Morning Pages Journal

Becoming: A Guided Journal for Discovering Your Voice

Austin Kleon’s Steal Like an Artist Journal

James Clear’s The Clear Habit Journal

V. Additional Journaling Resources

The Most Important Ritual You Can Practice This Year

14 Ways To Make Journaling One Of The Best Things You Do

Prepare in the Morning, Review in the Evening

The Most Important Thing You Can Do Each Day

What’s All This About Journaling?

Virginia Woolf on the Creative Benefits of Keeping a Diary

Celebrated Writers on the Creative Benefits of Keeping a Diary

The Most Important Things To Think About