By: Stephen Hanselman

The English language has done a great disservice to two of ancient philosophy’s greatest schools—Stoicism and Epicureanism. In the case of Stoicism, its popular meaning today suggests little more than a stiff-upper-lip, hyper-rational, emotionless automaton, not unlike the Star Trek character Mr. Spock. Similarly, Epicureanism’s popular meaning evokes a kind of sordid indulgence in food, drink, and bodily pleasures, not unlike Bluto Blutarsky in Animal House.

Both images are exactly the opposite of how the founders of the schools lived and what they taught.

Just as Stoicism was never a philosophy of emotionless calculation, so Epicureanism was never about hedonistic excess. In both cases, these popular misunderstandings would arise from caricatures peddled by much later members of the schools against each other. While differing substantially and despite how the two schools would eventually caricature each other, they were at the outset much more like sibling rivals fighting for attention in the cradle of Athenian philosophy.

Let’s first start with what the two schools shared.

Both Were Philosophies of Life, Focusing on the Care of the Soul, and Practical Wisdom

Let nobody put off doing philosophy when young, nor get tired of doing it when old. For no one is too young or too old to secure the health of one’s soul. — Epicurus

Epicurus founded his school in 306BC in Athens, just five years before Zeno would branch out from his studies with the Cynics and Megarians to establish the Stoic school in 301BC. Both men were launching new schools against the two long-established juggernaut schools of Plato and Aristotle. Both were led by charismatic thinkers brimming with new ideas about our connection to each other and how to achieve a more peaceful existence in a turbulent time.

We know from Epicurus’ letters (referred to by Diogenes Laertius) that the Stoics were originally also named for their charismatic leader, being first dubbed “the Zenonians.”

Both schools fashioned themselves as philosophies of life, focusing on the art of living. Both schools saw themselves as offering a fundamental therapy, or care of the soul. And both put practical wisdom (phronesis) at the core of their teachings. Both schools favored self-control and moderation to help reduce anxiety and increase tranquility.

So far, so good, right?

Pleasure/Pain vs Virtue Alone

One should laugh, philosophize, budget, arrange all other personal affairs, and never stop uttering the correct philosophy. — Epicurus

When it came to defining happiness, however, the two schools moved in opposite directions.

Epicureanism focused on the pursuit of pleasure, within the bounds of moderation, and the avoidance of pain. To the Stoics, who were influenced by both Socrates and the Cynic tradition, equating pleasure with the Good and pain with Evil was just poor thinking. They took a more austere path to happiness, focusing instead on virtue alone as the way, denying that the Epicurean pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain could ever bring true happiness. For their part, the Epicureans rejected this kind of asceticism, but they still were not unregulated hedonists. They shared the Stoic belief that wisdom and virtues like self-control and moderation are a necessary part of happiness but disagreed that virtue alone could guarantee it.

This difference led the Epicureans to emphasize the private virtues, urging their adherents to withdraw from the illusions of the political world, joining together with like-minded friends in a garden where they could practice a regimen of modest pleasures and fellowship. Here, they felt, one could avoid all the pains of life—hunger and thirst, heat and cold, the fear of war and death. In the world of Alexander the Great’s warring successors, with Athens under garrison for much of the 3rd century BC, this was an attractive proposition.

To the Stoics, whose philosophy was formed not in the refuge of a garden but in the open market of the Athenian agora, this kind of retreat into a private morality made no sense. They felt that the fullness of virtue encompassed our social roles and duties and involved justice as more than a mere byproduct of some utilitarian social contract. No, said the Stoics, it wasn’t the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain that would bring happiness, but only a pursuit of a fuller virtue that could bring happiness—one that did not depend on internal feelings of comfort or discomfort, or any external sources of those feelings.

Materialists, But with Opposing Physics

So, the two schools set different goals for the art of living. Part of the reason for this came from their understanding of nature. Their physics, while both materialist, were quite different. Both schools believed that material bodies were the only thing that existed, and denied any realm of forms or immaterial things. The Stoics believed there were other real things like time/space, void, and meaning, but that these didn’t exist in the way that bodies do. Epicurus taught his followers that “the totality of things is bodies and void.” What made up these bodies is where the two schools really differed.

Building on the atomism of Parmenides, Leucippus, and Democritus, Epicurus saw a world of blind atoms interacting without reason or purpose—indeed, it was the random “swerve” of atoms that accounted for their collision and ultimate gathering into larger bodies. On this point, they departed from the determinism of Democritus’ atomism, and used the swerve to account for our free will. Our senses depend on these atoms, and every sensation is a true event—error only arises in our judgments about these events. We are living in a random swirl of atomic interactions and must use our senses and judgments to gain better knowledge about the world. In addition to our senses and judgments, we have our feelings by which we apprehend pleasure and pain. For Epicureans, the gods were merely a construct of our minds. However, Epicurus taught that atheism itself is a form of lunacy that only brings trouble. In practice, he was an agnostic for the purpose of less conflict.

Stoic physics, while sharing a belief in material bodies, rejected random movements of atoms and instead saw a fiery divine rationality thoroughly mixed throughout the entire material universe. God and nature were one and the same thing. They saw an order and purpose to the universe, and that we as individuals shared in this rational order. The Stoics believed there was a pre-determined quality to the cosmos, but insisted that within it, we very much have a free will to choose whether our individual natures will be in accord with nature or not. How we decide this has everything to do with our happiness in life—their physics led them straight to the seeds of virtue they believed were implanted in us all, and to the imperative of developing them in all that we do.

The Oldest Disputes In The World: Religion and Politics

So with these doctrinal differences, it’s not surprising to see the first flashes of conflict between the schools happened around the oldest subjects of dispute in the world: religion and politics.

The main point of conflict on religion between the schools was the Stoic belief in providence. The Epicureans believed that if the gods exist, their blessedness would be upset by having to be involved with human affairs, messy as they are. They held an anthropomorphic view of the gods as human constructs with lessons to teach us, but not much more. The Stoics, by contrast, saw divine involvement in the creation and function of the universe and in our human lives. They rejected any talk of gods being human projections. In fact, we humans are rather more like divine projections in the Stoic view—if you realize that for the Stoics there is no transcendent God living in another realm. Aristo, one of the early renegade Stoics, saw the Epicurean teachings on religion of such students of Epicurus as Metrodorus as impious and creating conflict with social norms.

Zeno taught that it was our obligation to engage in the public sphere by taking up the duties of social office and politics—we are only excused from this effort when we are no longer able to do it. By contrast, Epicurus told his followers to pursue just the opposite path—to keep their heads low pursuing the principle of lathe biosas, basically to live without drawing attention to yourself. His position wasn’t without appeal and benefit in the rough and tumble world of warring generals and the rising monolith of Rome.

Diogenes Laertius relates a story from Epicurus about how when Zeno was invited to the court of Antigonus Gonatas II (son of Demetrius the Besieger and grandson of Alexander’s most fearsome general, Antigonus the One-Eyed), he (like a good Epicurean!) denied the invitation. Instead, in keeping with his belief in the obligation of service to government, he sent his personal scribe Persaeus, which no doubt earned the scorn of Epicurus (and hence the mention in his writings). The Epicureans were undoubtedly critical of a philosopher trying to curry favor with the Macedonian royal court. Persaeus would go on to be appointed by Gonatas to the position of archon in Corinth and he would die on the battlefield protecting that city-State in 243BC. Another of Zeno’s students, Sphaerus, would be in service of the Spartan king Cleomenes III in his attempt to reform the Spartan constitution to increase the number of land-holders and make a more fair society. That effort would end in defeat and Cleomenes would flee to Egypt with Sphaerus following him to the court of Ptolemy Philopator IV.

So, with these very differing ideas of political engagement it isn’t surprising that in 155BC, when Athens would send the heads of the great philosophical schools to Rome as ambassadors on its behalf, the Epicureans were the only school to skip out.

But from their garden and the gardens of many others, Epicureanism would nevertheless find its way into Roman public life.

Stoic Magistrates and Epicurean Confidants

As Rome grew in power, the Stoics came increasingly into political service, training the rising young nobles in philosophy and preparing them for public service. Panaetius, the last official head of the Stoic school in Athens, was the first to create a kind of ethical manual for these young and ambitious figures. One of his brightest students, Publius Rutilius Rufus, became a renowned soldier and ultimately gained responsibility for the training of Roman troops and served in public office trying to fight the corruptions of Marius and the equestrian tax farmers who were bleeding the Roman state and its provinces dry. Eventually Rutilius was brought up on charges and run out of Rome, when he retired to Smyrna, the city he was fraudulently charged with bilking, they offered him citizenship with open arms.

Interestingly, when Rutilius arrived in Smyrna it was with his dear friend and confidant, the Epicurean Opilius Aurelius. It would be a friendship between the two schools that would continue, despite their periodic conflicts.

One such conflict came around 100BC when Apollodorus, the powerful head of the resurgent Epicurean school (known as “the Garden Tyrant”), began to smear the reputation of Chrysippus, Stoicism’s towering third leader. This outraged a Stoic named Diotimus who proceeded to forge a series of 50 licentious letters in the name of Epicurus that to this day gave the school its undeserved depraved reputation.

Despite such efforts to hold Epicureanism back, the first philosophical works to appear in Latin were by Epicureans, including Amannius, Rabirius, and Catius—each treated with disdain by Cicero in his Academica and Tusculan Disputations. Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, filled with Epicurean ideas, also appeared during this time and was hugely influential in Roman life. Cicero had studied with the Epicureans Phaedrus and Zeno of Sidon (who prosecuted Diotimus) and his best friend and most trusted confidant was Atticus, another prominent Epicurean. So, despite the Epicurean lathe biosas (living secretly), the Epicureans were gaining social influence in Rome even as they rejected political office.

One surprising Epicurean who did not reject political office was Julius Caesar. His modesty, sharing with troops, and clemency with enemies were all Epicurean traits that set him apart from other generals like Pompey and Mark Anthony. He believed, like Epicurus, that money was to be used and not stored up for oneself. Epicurean practical wisdom (phronesis) held that we should look out for the economic well-being of our friends, which Caesar certainly did. He kept friends at all costs, and stood by Brutus even as the sometime Stoic plotted against him. He wanted to forgive Cato, even as the Stoic amassed troops against him.

Caesar’s father-in-law, the powerful consul and censor Calpurnius Piso was also an Epicurean. It was in his villa that the great Epicurean intellectual Philodemus came to reside, and his library which remained there in Piso’s Villa after his death was eventually entombed by Mount Vesuvius in 79AD. Now known as the Villa of the Papyri, this Epicurean library references one philosopher more than any other: the Stoic Diogenes of Babylon, who had headed the famous embassy to Rome in 155BC. The sibling rivals were still at it.

Another surprising appearance by an Epicurean in Roman life is that of Cassius, who was the lead conspirator with Brutus and others in the plot to kill Caesar. Not exactly the kind of “secret living” that Epicurus had in mind. Ironically, Caesar’s Epicureanism likely contributed most to him ignoring the superstition of the Ides of March and showing up to his execution.

After the death of Caesar and the rise of Imperial Rome, the Stoic philosopher Seneca would come into the court of Nero where he wielded great power. During his service to Nero he had a great Epicurean friend and confidant, much like Rutilius and Cicero before him, named Serenus.

It was during Seneca’s two attempted retirements (62 and 64AD), that we can see him struggling with his withdrawal from public life. In his book On Leisure (dedicated to Serenus) and in the first 30 or so of the Moral Letters, he seems to be in dialogue with the notorious quietism of the Epicureans as he wrestles with his abandonment of life at court. To avoid looking like he’s crossed over to the Epicurean side he begins to articulate a vision of leisure as serving “a special cause”:

“The two sects, the Epicureans and the Stoics, are at variance, as in most things, on this matter also; they both direct us to leisure, but by different roads. Epicurus says: ‘The wise man will not engage in public affairs except in an emergency.’ Zeno says: ‘He will engage in public affairs unless something prevents him.’ The one seeks leisure by fixed purpose, the other for a special cause.” (On Leisure, 3.3.2-3)

“Nature intended me to do both—to be active and to have leisure for contemplation. And really I do both, since even the contemplative life is not devoid of action.” (On Leisure, 5.8)

“…Contemplation is favored by all. Some men make it their aim; for us it is a roadstead, but not the harbor.” (On Leisure, 7.4)

This “roadstead” for Seneca was a time to use his writings to leave a benefit to those, like Lucilius, who might be able to make use of their advice. He knows he is living in a world without a safe harbor, and that despite all the promises of the Epicureans, whom he cites more than 80 times in his work (and Epicurus 64 times, more than any other philosopher), we must find a way through philosophy to turn words into works:

“Philosophy isn’t a parlor trick or made for show. It’s not concerned with words, but with actions. It’s not employed for some pleasure before the day is spent, or to relieve the uneasiness of our leisure. It shapes and builds up the soul, it gives order to life, guides action, shows what should and shouldn’t be done— it sits at the rudder steering our course as we vacillate in uncertainties. Without it, no one can live without fear or free from care. Countless things happen every hour that require advice, and such advice is to be sought out in philosophy.” (Moral Letters, 16.3)

The contemplative life is no longer an end unto itself, an Epicurean private pleasure, but as Seneca writes to Serenus, merely “a listless, imperfect good” (On Leisure, 6.2). For Seneca, leisure, or the withdrawal from public business, is really about the painstaking work that remains to be done so that we can bring benefits to ourselves and to others.

Seneca’s writings are ironically a testament not only to the power of Stoicism, but also to the enduring influence of its sibling rival, Epicureanism.

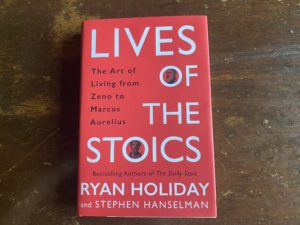

By: Stephen Hanselman, co-author of The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living and Lives of the Stoics, which is available for pre-order and is set to release on September 29!